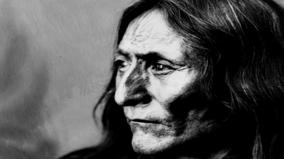

Les événements de Restigouche

Les 11 et 20 juin 1981, la Sûreté du Québec mène des rafles dans la réserve de Restigouche, en Gaspésie. En cause : les droits ancestraux de pêche au saumon des Micmacs. Les restrictions que le gouvernement québécois tente d'imposer sur cette pêche, source d'alimentation et de revenus pour les Micmacs, ont soulevé colère et consternation. Lancé en 1984, ce compte rendu coup de poing de l'intervention policière a fait connaître Alanis Obomsawin à l'international. Le film comprend un échange mémorable entre le ministre des Pêches, Lucien Lessard, qui a ordonné les rafles, et la réalisatrice. Des décennies plus tard, …

Details

Les 11 et 20 juin 1981, la Sûreté du Québec mène des rafles dans la réserve de Restigouche, en Gaspésie. En cause : les droits ancestraux de pêche au saumon des Micmacs. Les restrictions que le gouvernement québécois tente d'imposer sur cette pêche, source d'alimentation et de revenus pour les Micmacs, ont soulevé colère et consternation. Lancé en 1984, ce compte rendu coup de poing de l'intervention policière a fait connaître Alanis Obomsawin à l'international. Le film comprend un échange mémorable entre le ministre des Pêches, Lucien Lessard, qui a ordonné les rafles, et la réalisatrice. Des décennies plus tard, Jeff Barnaby, réalisateur de Rimes pour jeunes goules, citera ce film comme source d'inspiration. « Pour moi, ce documentaire a cristallisé l'idée que les films peuvent être une forme de contestation sociale... Tout a commencé là, avec ce film. »

-

directorAlanis Obomsawin

-

producerAlanis ObomsawinAndy Thomson

-

scriptAlanis Obomsawin

-

narrationAlanis Obomsawin

-

executive producerRobert VerrallAdam Symansky

-

cameraRoger RochatSavas Kalogeras

-

soundYves GendronBev Davidson

-

editingAlan CollinsWolf Koenig

-

sound editingBill Graziadei

-

animationRaymond Dumas

-

sound mixerJean-Pierre Joutel

-

music editingDiane Le Floc'h

-

songÉdith Butler

Education

Ages 10 to 17

Geography - Territory: Indigenous

Indigenous Studies - History/Politics

Indigenous Studies - Issues and Contemporary Challenges

Social Studies - Law

In class discussion, consider why the Quebec government decided to restrict salmon fishing on the Restigouche River by the Mi’kmaq. Was this decision lawful? Was this decision justified? Have students comment on the treatment of the reserve members by the QPP. Discuss the aftermath of the raids, in terms of vindication.