La face cachée des transactions

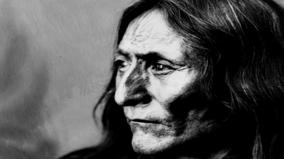

Le 300e anniversaire de la Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson, en 1970, n'a pas été une occasion de réjouissance pour tous. Narré par George Manuel, alors président de la Fraternité des Indiens du Canada, ce film majeur fournit des perspectives autochtones sur la compagnie, dont l'empire commercial de la fourrure a favorisé la colonisation de vastes étendues de terres dans le centre, l'ouest et le nord du Canada. Le contraste entre les célébrations officielles, avec la reine Elizabeth II parmi les invités, et ce que les Autochtones ont à dire sur la façon dont La Baie les traite, est frappant. …

Details

Le 300e anniversaire de la Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson, en 1970, n'a pas été une occasion de réjouissance pour tous. Narré par George Manuel, alors président de la Fraternité des Indiens du Canada, ce film majeur fournit des perspectives autochtones sur la compagnie, dont l'empire commercial de la fourrure a favorisé la colonisation de vastes étendues de terres dans le centre, l'ouest et le nord du Canada. Le contraste entre les célébrations officielles, avec la reine Elizabeth II parmi les invités, et ce que les Autochtones ont à dire sur la façon dont La Baie les traite, est frappant. Sorti en 1972, le film est coréalisé par Martin Defalco et Willie Dunn, membres de l’Indian Film Crew, une équipe de production entièrement autochtone créée à l'ONF en 1968.

-

directorMartin DefalcoWillie Dunn

-

participantDuke RedbirdWalter DeiterIsaac BeaulieuGeorge MunroeHoward AdamsEdward ThompsonBennett RedheadWalter GordonDave CourcheneHenry JackNoel StarBlanketWalter CochraneWillie Dunn

-

executive producerGeorge Pearson

-

commentaryDavid Wilson

-

editingDavid Wilson

-

photographyJean-Pierre Lachapelle

-

soundJean Guy Normandin

-

sound editingJohn Knight

-

re-recordingMichel Descombes

Education

Ages 14 to 17

Indigenous Studies - Issues and Contemporary Challenges